SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM FOR MUCH MORE

Thom Gambino and the

UMANO ORCHESTRA

Thom Gambino and the

UMANO ORCHESTRA

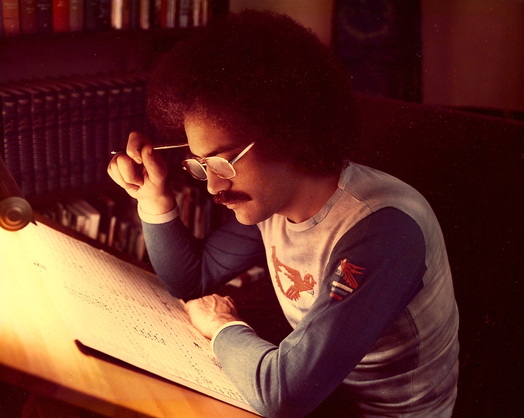

In 1978, Thom and Lorry Gambino founded THE UMANO ORCHESTRA, a 26-piece jazz-rock ensemble which utilized many cross-cultural musical influences. They also formed THE UMANO FOUNDATION, a non-profit institution which fosters the establishment of a World Federation under real, enforced international law. The Umano Orchestra and Foundation were named after Gaetano Meale, an Italian judge who came into his own at the turn of the 20th century. His tireless work in cross-cultural studies and the feasibility of a World Center of Communications were explained in his 1912 book entitled "Essay on the International Constitution." Judge Meale's pen name was UMANO, Italian for human being. His concepts were first introduced to Thom & Lorry when they (by chance) found a book by legendary journalist Lilian T. Mowrer entitled "Umano and the Price of Lasting Peace." They contacted the elderly Mrs. Mowrer and began The Umano Foundation with her. The Gambinos carry the torch for her and Judge Meale's dreams to this day. The orchestra also embodied Umano's concept. It was a group of men and women from many different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and the music reflected that. The music has a unique and mesmerizing blend of power that can either hypnotize you with its beauty or make you sit up and feel its explosive groove.

Over the years, hundreds of the best jazz, rock, Broadway, television, recording and symphonic musicians in the New York City area have played with The Umano Orchestra. We salute them all for their donation of time, compositions, musicianship and wisdom. We thank them all for their friendship.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Hear our music here.

See our captioned pictures here.

THOM GAMBINO and The UMANO Orchestra

EARTHLING MUSIC

Instrumentation: 5 saxes, 5 trombones, 5 trumpets, 4 French horns,

2 guitars, piano, bass, drums, 2 percussionists, singers.

LONG TIME NO FEEL** (Composed and arranged by Thom Gambino) Solos: Jim Satten, guitar; Thom Gambino, alto sax. (Rick Tell: engineer, Delta Studios recording)

WAKE UP** (Composed by Stephanie Chapman, arranged by Thom Gambino) Laura Theodore, vocalist; Marc and Kim Gambino, backup vocals; Thom Gambino, alto sax. (Michael Finlayson: engineer, Unique Studios recording)

IF I COULD TOUCH THE STARS** (Lyrics by Stan Bronstein and Flo Moree, music and arrangement by Thom Gambino) Laura Theodore, vocalist; Thom Gambino, alto sax. (Michael Finlayson: engineer, Unique Studio recording)

COULEURS D’ANGELE (Composed and arranged by Ronald Aprea) Solos: Thom Gambino, alto sax; Pam Fleming, trumpet. Early Autumn Productions, ASCAP. Used with permission. (Live recording)

RIGA SUITE** (Composed and arranged by Thom Gambino) Solos: Thom Gambino, alto and soprano saxes; Marc Tobac, piano; Anatole Gerasimov, tenor sax. (Live recording)

Three Movements:

1. NIGHT TRAIN TO RIGA

2. THE CAMP

3. A SONG FOR IVAN’S CHILDREN

Thom Gambino returned from a trip with the Joffrey Ballet to the Soviet Union in December, 1974. Riga, the capitol of Latvia, had a special affect on him and he expressed it in his book "Nyet: An American Rock Musician Encounters the Soviet Union." This excerpt from Thom's memoir, "The Vagabonds: A Musician's Odyssey," explains the meaning of the three movements:

"Riga Suite" was recorded in a loft on Monday, October 18, 1976. Don Pinto’s Brownie’s Revenge, 27 strong, premiered “Riga Suite” during our regular gig at Trude Heller’s. “Riga Suite” had three movements: “Night Train to Riga” was an up-tempo piece featuring the saxophone section. I played soprano sax lead and took a solo, followed by one by pianist Mark Toback. “The Camp” was a slow, ponderous lament for those prisoners that Penny Curry saw in the concentration camp. “A Song For Ivan’s Children,” featuring a spunky ensemble section, was reminiscent of the snowball fight we had with the children in the park in Riga. Anatole Gerasimov, a recent Russian arrival, played the tenor sax solo.

The entire suite was taped in one take on a four-track machine that night and included on Don's roster. Don wanted to use the tape to drum up more work for his orchestra. He plugged my book at least once a night on every gig for an entire year.

TEXAS PEARL (composed by Jean Fineberg, arranged by Thom Gambino) Solos: Jean Fineberg, tenor sax; Rick Ulfik, piano. Bodybuilder Music, ASCAP. Used with permission. (Gene Perla: engineer, Studio recording)

MEDIEVAL GARDENS** (Composed and arranged by Peter Piacquadio) Solos: Thom Gambino, alto sax; Bob Roman, flute; Mitch Endick, baritone sax; Marco Katz, trombone; Mike Holover, trumpet; Pam Fleming, flugelhorn. (Gene Perla: engineer, Studio recording)

I CAN ONLY GIVE YOU A SONG** (Composed and arranged by Thom Gambino) Solos: Thom Gambino, flute; Dom Carelli, trombone. (Rick Tell: engineer, Delta Studios recording)

SHAMAR RISING** (Composed and arranged by Jack Bashkow) Solo: Jack Bashkow, tenor sax. (Rick Tell: engineer, Delta Studios recording)

YESTERDAY’S GOODBYE** (Composed and arranged by Thom Gambino) Solos: Thom Gambino, alto sax; Mike Molaro, trumpet; Ray Maldonado, trumpet; Bart McLaughlin, drums. (Rick Tell: engineer, Delta Studios recording)

UMANO Speech

by Thom Gambino

In the spring of 1978, I gave a speech to a conference of Non-Governmental Organizations. That NGO meeting was among many that took place during the United Nations General Assembly’s Special Session on Disarmament and provided a great way to hear the ideas of those who weren’t part of the U.N.’s formal structure. I said to the gathering:

Beginning with the post-World War Two generations, there have been remarkable changes in attitudes concerning war and peace. Many young people feel cheated by their forebears, because they have been unable to live any part of their lives without the threat of nuclear weapons. Others, quite frankly, have completely tuned out, either because they feel alienated from a technological society that diminishes their sense of individuality, or because the specter of facing the reality of the destructive nightmare we live under is too much to bear.

But the common thread they share with the more concerned members of the older generations is a genuine desire to find a lasting solution to the problem that is at the heart of all human difficulties: violence and violence magnified – warfare.

When I returned from the Joffrey Ballet’s 1974 tour of the Soviet Union, I faced a serious personal crisis. My intuitive reaction to the Soviet government was negative and I made no attempt to hide it in my book “Nyet.”

But my attitude clashed with my desire to find common ground with other cultures – a discord aggravated by Soviet citizens who, at great peril to themselves, told me of the far more serious injustices they must endure in their lives.

Without knowing the psychological term, I had begun a process called cognitive dissonance – the resolving of two or more seemingly contradictory beliefs into a rational new attitude.

Did I still believe in disarmament at a time when the Soviet Union is following our Vietnam lead and is attempting to build an empire in Africa? Did I believe in coexistence when I saw so many Soviet artists and citizens hungry and oppressed? Did I still believe the U.S. should cut its arms budget and allow the Russians, who would surely view us as weak, to fill the power void we would leave? Was I being paranoid about the Soviet Union? Or were my observations accurate? Did I still believe it was possible to eliminate warfare?

These questions troubled me until I made a fateful trip to Washington to discuss my book on local radio and television.

In Washington, I met Robert Burgener, who was a psychologist, public relations expert, former professor of intercultural relationships at Tokyo’s Sophia University, and a former ABC News producer. We decided to form a foundation to institute new psychological studies to break down barriers between cultures. We also wanted to explore how music could be more effectively used to foster a sense of world community. We only lacked a name for our novel concepts.

When I returned to New York, I found a book entitled ‘Umano and the Price of Lasting Peace,’ by Edgar and Lilian Mowrer. The book cohesively defined ideas and attitudes only vaguely expressed by those concerned with peace and the ecology of the planet.

About the turn of the century, Gaetano Meale, the youngest member of the prestigious Milan bench, renounced his judgeship, assumed the pen name ‘Umano’ (human being, humane), and devoted the rest of his life to the search for permanent peace and the abolition of warfare.

Umano believe war was caused by internal despotism within countries and by international anarchy abroad. He ultimately proposed an organization far stronger than the United Nations, at a time when most people considered the League of Nations a radical concept.

In his ‘Positive Science of Government,’ Umano called for a World Federation based on an International Constitution. The plan would eliminate national armies and armaments, and would institute a World Parliament.

Truly one of the first people to think as a world citizen, Umano said international law backed by just enforcement must be established, while we begin studies to break down the barriers between cultures. Along with Hendrik Andersen, an American sculptor living in Rome, Umano proposed a World Centre of Communication, an international city devoted to the arts, sciences, and the search for a peaceful world economy, where money formerly used for defense would be used to end poverty, racism and injustice. His city, undefended and run entirely on a peacetime economy, would be a model for the rest of the planet to study and emulate.

New York could be that city.

Two years before Umano’s death, eight leading Italian senators proposed him as a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize (1925), but the judges preferred ‘practical steps for relaxing tensions’ to Umano’s ‘theories he calls science.’

So, the prize was divided between Charles Gates Dawes, banker and initiator of the Dawes Plan for German Recovery, which formed the basis for Hitler’s war chest, and Sir Austen Chamberlain, main author of the ineffective Locarno Pact, a scrap of paper, the detente of the Twenties.

Rob Burgener, my wife Lorry and I thought Umano was the perfect name for our foundation and 25-piece orchestra. We wrote Lilian Mowrer, co-author of the Umano book. During a weekend visit to her New Hampshire home, Mrs. Mowrer agreed with our plans, and The Umano Foundation and Orchestra were born. We later recruited Mona St. Leger, a Washington banker and daughter of a Lebanese diplomat.

We then traced the World Federation concept through history, from the writings of Aristotle, Cicero, Aquinas and Hobbes to the historic Freud-Einstein letters commissioned by the League of Nations.

The flow of history is clear. Tribes stopped fighting other tribes when they agreed on a code of mutual conduct and banded together into cities. Then cities fought other cities and later banded together into states. Then states fought states, until a code of law was formed to unite them into nations.

We have gone beyond nations fighting nations. We now live on a planet where worldwide alliances fight each other. This must come to an end. We must bow to history and take those steps which acknowledge our planet’s fragile ability to sustain nuclear war…

It is only natural that The Umano Orchestra would be a part of this movement, for artists concerned with creation should work to end destruction. However, The Umano Orchestra is far more than that. It is a celebration of the music of one world. Not only do our musicians represent almost every culture, but the joy and exuberance they exhibit just as human beings is a reaffirmation that the world is headed for far better things. I am proud of them. I love them.

We hope to build a worldwide audience across the entire age spectrum. We further hope that our music will foster a greater sense of world community and humanity.

Eventually, the orchestra will fund our foundation. We will also seek endowments and general contributions. While the orchestra personnel is set for the foreseeable future, we still need more bright, sensitive, original music from composers, arrangers and lyricists in the jazz-rock field. This is a chance for those artists who believe in peace to work for a non-ideological and definitive plan to eliminate warfare. Also, The Umano Foundation is an open membership group. All are invited to join.

Obviously, we could use concert commitments to provide an income for our 802 musicians, who could then work full-time for our foundation and world peace.

There are those who feel it is wrong to mix art and political action. I cannot disagree more. We are living to help humanity. The nations of the world now spend one billion dollars a day on armaments. We could offer other equally stunning statistics we have discovered while working at the U.N.’s current disarmament conference. We think our plan is the most rational approach to our human dilemma. We will join others in programs designed to educate the public to our proposals.

This is a wonderful time to be alive. For the first time, we are able to communicate with anyone anywhere on the planet. For the first time, we can view history as it happens. We have begun to plan for the post-military-industrial age. We have left this planet and begun to explore the solar system. Hopefully, we will begin our habitation of outer space as human beings, not as nationals on any one country. And, hopefully, we will have begun to solve our more fundamental problems on our planet, such as racism, poverty, and – that scourge of mankind – warfare. For nothing breeds war better than war itself.

We answered the terror and destruction of World War One with the formation of the League of Nations, an extremely weak institution doomed to failure from the start. Because of our human condition at the time, we continued to practice old-fashioned balance-of-power politics, but we were armed with a technological base that required a new set of ethical principles and bold new concepts of international community.

We failed the test, were plunged into World War Two, and paid for our folly with the lives of millions of people. And, although each life lost was as precious as the other, we will never be able to gauge how many Einsteins, Freuds, Kings and Umanos were among them.

The United Nations was our response to the Second World War. While beautiful in concept, the U.N. has no executive power to outlaw confrontations and has no power to enforce peaceful arbitrations. At this stage of its development, it can only be considered a steppingstone toward a true World Federation.

We suspect the general populations of the world scorn the U.N. not so much because they have little sense of international identity, but because they wisely perceive that any body unable to command respect for its utterances is headed for failure.

At the heart of our proposals are certain basic rules which are universal in concept and close to the core of almost every human culture. We should love one another. We cannot and we should not kill. Whether humanity accepts those edicts as commandments or as codes of ethical behavior is not nearly as germane as its universal acceptance and its beautiful simplicity: Human beings have a right to a nonviolent existence with dignity.

At this time our failure to act may not lead to the end of humankind, because military experts have never yet contended we have reached that level of overkill. But, in the event we stumbled into a nuclear war, Western and Eastern Civilization, the sum total of our accumulated knowledge and human organization, would surely not endure. And we would have failed to live up to the trust which humanity’s ancestors have placed in our hands.

We refuse to accept such an outcome. We view the emerging intolerance of warfare as a sign of tremendous hope and joy, which are the only true catalysts for flourishing peaceful change.

We ask the peoples of the world to join hands and begin a new age, more peaceful and stable than any other that has gone before. For, as Umano once said, “ Every day, on this planet, a human being, struggling with some great idea, is slowly dying because of others’ neglect, arrogance or selfishness. And his idea, for lack of help, dies with him to humanity’s great loss. Here is your chance! And there is still time!”

_____________________________________

My remarks weren’t well received by many of the groups there. Many of them, such as the Women’s League for Peace and Freedom, were far to the left and always found some way of damning the American government’s point of view, while excusing the excesses of the Soviets. In days past, I would have been more gullible in accepting that stance, but not since my experiences in the Soviet Union with the Joffrey Ballet and the valuable tutelage I received from Lilian Mowrer.

I couldn’t help but notice the two unsmiling men who sat in the second row and took notes on everything and everyone involved in the meeting that day and never applauded.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

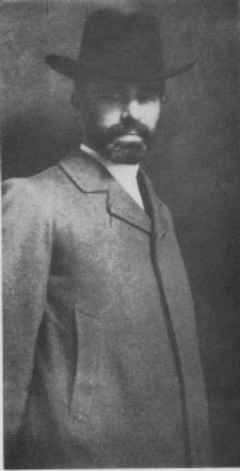

Umano in his prime. He always

dressed very plainly.

Umano in his prime. He always

dressed very plainly.

Notes on Umano: His Life and Work

(Gaetano Meale, 1858-1927)

By Lilian T. Mowrer (Written in 1982)

Gaetano Meale was a brilliant Italian law student and the youngest judge ever appointed to the prestigious Milan bench.

At an early age, he realized that human progress–everywhere–was hindered by that ever-recurring scourge–war–and the threat of war.

He noted that national governments kept peace in their own countries by force of law. “Therefore, it would be futile to urge world peace, when there is no overall authority powerful enough to establish and enforce whatever agreements countries made with each other.”

Might does not make right–But might makes law, he said. Peace is the product of law–It was the lawlessness in which nations lived–the international anarchy–that was the root cause of war.

His solution was presented in a ninety-page pamphlet, “The End of Wars Through the Federation of the Peoples” (1889). He was far too hardheaded to imagine that national struggles would ever cease. He ridiculed prevailing Socialist pacifism as unrealistic. Men would always disagree (Life itself was a struggle). But it need not be on a battlefield.

An International General Assembly of elected delegates should be formed–the individual numbers depending upon the relative strength of the country they represented. (No one would be likely to accept a substitute for war if it did not in some way approximate a country’s strength and fighting force.)

Therefore, he concluded that a weighted index of voting, primarily based on national population, educational level, economic and industrial development be introduced.

International disputes would be tried, judged and settled by this assembly, armed, as it would be, with adequate military and legal power to enforce its decisions.

It was not immediate peace that he was offering. It was a choice of ways of dealing with urgent threats: in a disorderly bestial manner. Or in a reasoned, legal and humane way.

The cost of this inestimable boon of ridding the world of war was only the surrender of a fraction of each country's national sovereignty–the right to make war. That’s all.

He found support for his ideas. Modern arms–even in Meale’s time–had taken all of the “fun” out of fighting. War was simply becoming too costly. Even the most belligerent people seemed ready to admit this. There did seem to be, argued Meale, a beginning of revulsion against warfare.

To succeed, Meale knew his Federation must keep its efforts strictly to its one great task–ridding the world of war–without straying into other fields. The Federation should not concern itself with feeding the hungry, etc. Such admirable efforts would speedily follow once the world ceased that inhuman waste of all its best elements by disastrous war.

Even with strict attention to its definite limitations, The Federation of Peoples would require great psychological preparation, since all change begins in the mind. His suggestions for this were naturally somewhat limited by contemporary lifestyle and social usage. But Meale especially emphasized the role historians should play:

Cease harping on old grudges, referring to countries as “friends” and “enemies.” Emphasize similarities among nations, as well as their differences. Above all, teach world history as well as national history. “The Earth is our common fatherland.”

He warned newsmen against blowing up trivialities into war scares.

He placed great faith in Italy’s youth–as yet “unperverted” by history. But, they should think more accurately about world events.

Before his advent, he maintained, “politics were as empirical as medicine had been before the study of anatomy–e.g. on a level with astrology, alchemy and witchcraft.” He was beginning to talk of the Positive Science of Government.

Meale’s “End to Wars…” was widely read, translated into French & English, discussed by the London Peach Society and by the Lombard Branch of the International Arbitration and Peace Society. He followed with an expanded version. His Federation, he explained, could begin modestly by the union of five or six European countries, which would probably attract the United States. Democratically-oriented monarchies would not be excluded.

Roughly about this time, Meale decided that his whole existence must be dedicated to his chosen work.

He resigned from his judgeship, renounced his name (lest his great ideal be sullied by dreams of vainglory), and, until his death, was known simply as UMANO (human being)–bent on ending world war for all time.

The announcement of the forthcoming great Second Hague Conference (October, 1907) offered him an unequaled opportunity. To all conference members, he sent his “A Dissertation on an International Constitution,” which contained his “Seven Fundamentals” for Lasting Peace:

1) The acceptance of force - i.e. the capacity to operate-as the essential basis of national and international government. But not just brute force. Mental, muscular and economic factors plus population numbers must determine the weighted index of national representation in an International Assembly, whose decisions would be a substitute for war.

2) A definition of political rights and duties.

3) The meaning of justice and injustice, equity and inequity.

4) The correction of accepted misunderstanding concerning liberty and independence.

5) The essence of despotism and of tyranny.

6) A description of representative government as it should be.

7) An explanation of how force, though never abolished, can be disciplined.

1) Government, he insisted, can only be the studied industry of the strongest living human beings, who, in exchange for rule, provide security and a share in the prosperity with the governed.

2) Justice is the scrupulous observance of the laws determining the rights and duties established between governors and the governed.

3) Justice, to be scrupulous, must be public, impartial, punctual and open to criticism. Just and unjust do not describe the good or bad nature of a law, but its legality or illegality.

4) Equity and inequity describe a law’s morality or lack of it.

5) Despotism is a regime which applies governmental strength in an arbitrary manner; it cannot permit liberty lest it be undermined, or overthrown.

About 1910, Umano made the acquaintance of an American sculptor living in Rome, Hendrik Christian Andersen, who had devoted most of his career and a sizable fortune planning A World Centre of Communication, which his massive statues were to adorn. An instant friendship began between the two men, each feeling the other complemented his own quest for world peace.

Henrik, at very considerable expense, had just published a book of almost Renaissance splendor-outlining his ideas, with all the architectural plans for the World Center. Five hundred copies had been presented to various heads of state and to world public libraries. He was now preparing a second volume elaborating on the legal and economic benefits of such a scheme. He asked Umano to write the legal section. Once more, fate seemed to turn favorably in Umano’s direction. His work would receive worldwide attention.

Although his views on limitation of national sovereignty and enforced international law had shocked some statesmen and international lawyers, his writings of citizen participation were greeted with enthusiasm.

After harshly reminding readers that a dictator’s despotism would never have been possible without “cowardice of the ruled,” he added that the greatest human conquests, including civilization, had been due to “peoples’ boldness and force. For readiness to die for others makes even the weakest strong.” He said people failed when they funneled their ideas into “idiot schemes.” They were bound to fail, since their perpetrators had no understanding of politics-only of partisan idiosyncrasies.

For the first time a newspaper of European renown, the conservative Paris Journal des Debats, wrote that “Umano’s solution (for world-peace)–both positive and practical–was based on ideas that deserve attention.”

When World War I broke out, both Umano and Hendrik redoubled their efforts. The latter’s vast correspondence over the years with eminent men of all nationalities now offered opportunities of personal contact.

American entry into the war, President Wilson’s Fourteen Points, and the League to Enforce Peace increased Umano’s belief that here, finally, was a world figure who understood that mere agreements for peace were not enough–Real power must be created since potential coercion would be essential in any future League. But Wilson was a moralist, not a man of wide political experience. He was quite unable to cope with nationalist leaders determined to “adjust their frontiers outwards,” as was customary with victors after most wars.

The ratification of the Versailles Treaty made only too clear the bitterness of lost opportunity. The League of Nations was to be composed of totally sovereign nations. Umano was convinced that this could only lead to another world war.

Crushed and almost hopeless, his disappointment hastened his early death. But, not until he drove himself to finish his Magnum Opus: “The Positive Science of Government,” a volume of 1,214 pages in which he reiterated so many of the warnings previously published.

It had taken the horror of the late Horrendous War to make humanity realize the “anarchic barbarity of national independence and sovereign rights.” Would a Second World War be needed to bring any corrective action?

“Humanity,” argued Meale, “resembled a man in convulsions lying in the street with sympathetic passersby, each offering suggestions for relieving his suffering. Till a ‘rebel priest’ insisted the man be taken to a doctor for professional examination and scientific remedy.” Another war seemed doomed to follow, he feared, “Since every great human benefit was always the product of the great effort required to escape a great evil.”

Two years before Umano’s death, eight leading Italian senators proposed him as a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize (1925). But the judges preferred “practical steps for relaxing tensions to Umano’s theories he calls science.”

So, the prize that year was divided between Charles Gates Dawes, banker, initiator of the Dawes Plan for German Economic Recovery. It later formed the basis of Hitler’s war chest.

The other winner was Sir Austen Chamberlain, main author of the ineffective Locarno Pact–a scrap of paper–the “détente” of the Twenties.

In October 1945, just 71 days after the explosion at Hiroshima, a group of far-sighted Americans, at the invitation of Justice Owen J. Roberts of the Supreme Court, met in Dublin, NH, to consider the possibility of total atomic war. (Secretary of State Stettinius had already testified in Congress that the U.N. could not prevent major war.)

In Dublin the early Federalists (Edgar Mowrer helped draft the original declaration) urged the creation of a Federal World Government, with strictly defined and limited powers to prevent war.

The chief difficulty in establishing this substitute for war was in estimating the potential power of each of the fifty-one different nations. Every effort was made to utilize the U.N. Charter–but that unrealistic one-nation-one-vote-approach simply would not work if applied to a country’s might on the battlefield.

One of the least controversial of the plans for coping with representation, was advanced and kept up-to-date by the distinguished lawyers Grenville Clark and Professor Louis B. Sohn of Harvard. Known as the Clarke-Sohn Category Plan, it proposed that the four giant nations, with population in the hundreds of millions (China, India, Russia and the USA) should all be given 30 votes each (although it was ludicrous to equate India’s war-making capacity, for instance, with that of Russia or the U.S.A.).

The next category, with 12 votes each (12 delegates, that is) would include nations in the 50-115 million range (Indonesia, Pakistan, Japan, Brazil, West German, Britain, Italy, France and Mexico).

This graduation process would continue down the population line, making five more categories with 8 per nation, then 6, 4, 3, 2 & 1.

The grand total of 700 delegates was large, but not much larger than the 630-member British House of Commons.

Countries showed a marked “touchiness” at having their “worth” assessed by other nations. But today’s computers could impartially assess masses of national data without giving offense.

Umano’s fundamentals for government included force–mental, muscular and economic–clearly showing that he felt population alone did not establish a country’s fighting power.

Computers could take into account educational level, industrial production and national wealth, even rating such imponderables as recent participation in international affairs, literacy levels and spiritual values.

As all this would have to be constantly revised, it would certainly spur improvements within nations. For a country could acquire more political power as its ratings climbed–and all nations could accomplish this without killing any of its neighbors.

Umano’s insistence that the General Assembly of his Peoples’ Federation stick closely to its appointed task was yet another instance of his unique political acumen.

Under pressure of ever-yet-more-terrible wars, peoples, he maintained, might well accept the verdict of some Overall Authority on the overwhelming subject of war vs. law. But, almost everyone would resent “a bunch of foreigners telling us what we can do about domestic affairs.”

Even as the Supreme Court of the United States is bound and limited to a certain degree, so must any future World Federation be most scrupulously limited to its peacekeeping tasks. By 1947, a Gallop Poll revealed that a majority of Americans desired a world government to control the forces of all nations, and by 1950 nearly one half the U.S. Senate and a sizable group of U.S. Representatives had advocated “a study of projects to end world anarchy.”

But as years went by, the older politically wise leaders died. Younger political amateurs headed the United World Federalists. They succumbed to the “accommodation policy” on matters of inspection and control of atomic weapons. They showed a marked indifference to the Communist takeover in China; and, before any world authority had been established they made unilateral disarmament one of their major policy planks.

At a Second Dublin meeting to celebrate their 20th anniversary, they issued a declaration affirming the imperative need for World Federation and world law. But, also calling for the establishment of a affiliated World Development Authority to mitigate economic “disparities between the ‘have’ and the ‘have-not’ nations,” since ‘poverty,’ they declared, “is one of the root-causes of war.’!!!

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Lilian at her home in Wonalancet, NH

Photo: Lorry Gambino

Lilian at her home in Wonalancet, NH

Photo: Lorry Gambino

Lilian T. Mowrer

(1889-1990)

Lilian Thomson Mowrer, President Emerita of The Umano Foundation, was born and grew up in London, England and was educated at Liverpool University, at the Paris Sorbonne, and the old Roman Sapienza. In 1916 she married foreign correspondent Edgar Ansel Mowrer, immediately joining him in Rome where they lived for eight years. She was decorated for meritorious work with the Red Cross in World War One. Then followed over twenty years of further assignments in Germany, France, Russia and Central Europe.

While in Europe, Lilian Mowrer was a regular contributor to English and American newspapers and magazines, and published her first book, “Journalist’s Wife,” in 1937, a bestseller translated into six languages. Other books are “Arrest and Exile, an American refugee story of Siberia”; “Riptide of Aggression,” an outline of World War Two and required reading at Harvard; “Concerning France”; “The United States and World Relations”; and a historical biography, “The Indomitable John Scott, Citizen of Long Island.”

Mrs. Mowrer’s book, “I’ve Seen It Happen Twice,” an account of her experiences before, during and after World War II, was published in 1969. Lilian and Edgar Mowrer’s collaboration, “Umano and the Price of Lasting Peace,” published in 1973 by Philosophical Library, is the definitive examination of Umano’s life and work–based on a close eight-year friendship with him in Italy and an international perspective gained over the years.

In 1940 the Mowrers left Paris just two days before the Germans marched in and they lived for 29 years in Washington, DC. They made side trips to the Far East and spent long quiet days in their home in a New Hampshire village. Edgar Mowrer, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and columnist for the now-defunct Chicago Daily News, died in 1977.

Two months later, Thom Gambino, NY musician, composer and author, wrote to the Mowrers, saying he had read their biography on Umano and that it had changed his life, bringing into focus all his own vague longings for world peace. He has devoted his life to promoting Umano’s ideas. Mrs. Mowrer collaborated with Thom and Lorry Gambino on the formation of The Umano Foundation and The Umano Orchestra.

Lilian T. Mowrer died on September 30, 1990. She was 101 years old.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

UMANO SAYS:

Culled from “The End of Wars Through the Federation of Peoples” (1889)

and other writings and lectures by Gaetano Meale (1858-1927)

UMANO SAYS: “Wars happen since there is nothing to prevent them. War is the result of International Anarchy.”

UMANO SAYS: “To preserve peace each nation must accept a single suprapower (for international affairs alone), just as it accepts a national government for domestic affairs.

“Already in the minds of distinguished men and women trembles the idea of a single fatherland, a complete Federal Union of Peoples embracing the WHOLE EARTH.”

UMANO SAYS: “Never forget that within nations, in the absence of government which keeps peace by force, citizens must defend themselves bodily.

Are individuals in good faith who accept representative government at home when they reject it internationally?”

UMANO SAYS: “Short of the millennium, force will continue to shape human relations. But force is not only physical; it is mental, moral and economic as well.

"In a ‘scientific’ democracy, application of force could remain latent. For even the weak become powerful through readiness to die.”

UMANO SAYS: “Remind those imbeciles disguised as lawmakers that the inability of nations to solve their internal and local problems is because the international anarchy causes them all to keep their hands forever on the sword.”

UMANO SAYS: “A Balance of Power temporarily preserves peace only so long as both sides believe themselves equal. But sooner or later, one side feels itself sufficiently stronger to risk armed conflict. Even a preponderance of power in the hands of an alliance is hardly more dependable…

“The basic question facing hundreds of millions of contemporaries who really wish to end war should be, why are they and their predecessors failing in his most essential task?

“Their motives have been--and are--compelling enough: these have constantly been love (and religion), righteous indignation, economics and fear–all with no substantial effect.”

UMANO SAYS: “The elimination of war (though not the spirit that causes it) is a practical, not a moral problem. Absence of war will not immediately bring world peace and justice for all. Life itself is a struggle. Human nature evolves with depressing slowness. From what we know of history, the Will to Power is virtually constant. Yet we can refrain from periodically destroying all the best and strongest in every nation.”

UMANO SAYS: “Government can only be the studied industry of the strongest human beings (accepting force, mental, muscular, and economic as the essential basis of government) who, in exchange for rule, provide security and a share in prosperity to the governed.”

UMANO SAYS: “Let those who deplore war come forward and learn how to stop it. Until the day when brotherhood and Christianity are no longer limited to the jargon of thieves and illiterates, wars will happen unless prevented. Hence the need for a Federal Union backed by force–the basis of all universal things, without which the Universe would be in chaos.”

UMANO SAYS: “How can one expect governments, committed to this permanent international lawlessness, to accept that fractional sacrifice of sovereignty inherent in an international Federation?”

UMANO SAYS: “What confusion in the minds of those who squawk for peace while talking about neutrality and independence, thus arguing for further international anarchy.” (Written in 1915, when Italy was still debating entering World War One.)

UMANO SAYS: “Moral obligations are regulated in ecclesiastical courts and are of voluntary execution. Legal obligations are regulated in judiciary courts.. and are of enforced execution. Let states..which are tired of anarchical uncertainty as to the fulfillment or non-fulfillment of stipulated agreements unite to create a legal supra-state such as will protect all countries and peoples.”

UMANO SAYS: “Preach peace whenever possible, but do not make the mistake of thinking that this will work without the realization of the only idea which will succeed...namely that of peoples working together in agreement.

“Such a great, unique, and certain solution of the problem of war and armaments must take the form of an International Federal Union, a Federation of Peoples.”

UMANO SAYS: “All human disputes, like everything else in nature, are always settled by force--the force of mind, body, spirit, and wealth. These elements are habitually present in every human contest. Positive politics therefore require that the strongest combination of these elements in each country should rule peacefully. International government can only prove scientifically successful in which the rulers really and continuously dispose of the obvious power to make themselves obeyed.”

UMANO SAYS: “With enforceable world law and sanctions prevailing, disputing countries can no longer resort to arms as the final solution to international disputes. “NO MORE SETTLEMENTS ON BATTLEFIELDS!”

UMANO SAYS: “International war can only be avoided permanently by peaceful rule of the really strongest.

“In short, what is needed is a world-authority–limited to deal only with matters of foreign policy and defense.” (In everything else, participating countries remain completely independent.) But they would be represented in the Federal Union proportionally to their real strength*--not according to population, land mass or merely one-state-one-vote.”

*(Today’s computers digesting massive national statistic could easily reduce this to a voting equivalent.)

UMANO SAYS: “To America destiny reserves the magnificence of pointing out the new future greatness, certainly not of Empire but of civilization and of race. To America then destiny also reserves, with the grace of escaping the abjection of decadence, itself a natural consequence of the magnificence of greatness, the grace of showing humanity how to escape it forever, how to cure itself radically and fully of the two State sores*, how to prevent the earth, before its death, becoming from pole to pole, one sewer of fallen peoples.”

*International Anarchy and Domestic Despotism

UMANO SAYS: “Every day, on this planet, a human being, struggling with some great idea, is slowly dying because of others’ neglect, arrogance or selfishness. And his idea, for lack of help, dies with him to humanity’s great loss. Here is your chance: AND THERE IS STILL TIME!”